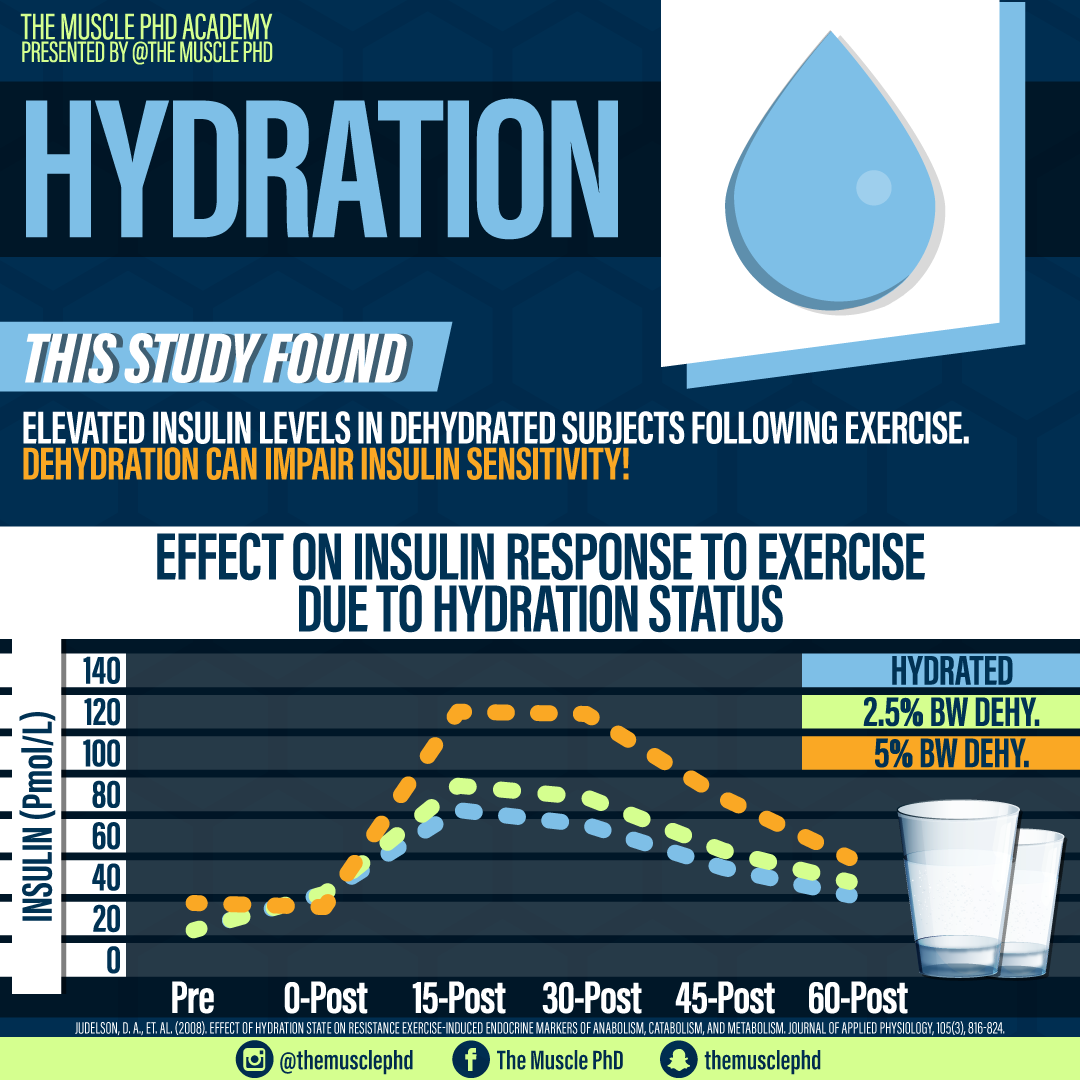

This study found that subjects who were dehydrated at 2.5% and 5% of their bodyweights had higher insulin levels following exercise. Dehydration can reduce insulin sensitivity which can impair muscle growth and overall gains. Drink 16oz of water before and after your workout and shoot for at least 2-3 liters of water per day to optimize hydration levels.