Introduction

We commonly hear the powerlifting community and other gym-goers talk about the importance of the lats in the bench press. At face value, this seems a little backwards. The lats are essentially pulling muscles whereas the bench is a pressing exercise. So, what gives here? Are the lats actually important for a big bench press? Let’s check it out.

Before we get any further, you might want to bone on up some biomechanics with our Physics of Bodybuilding article here. That might help explain some of the terms we’re using here.

Lat Anatomy and Function

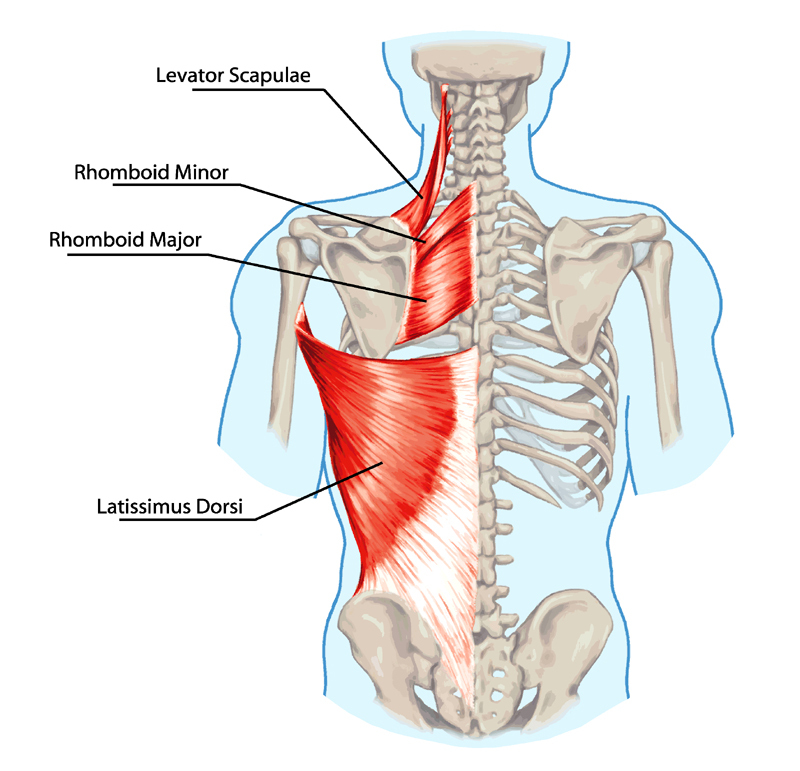

Many bodybuilders have a pretty good idea of where-ish their lats are. The lats are the big fan-shaped muscles in our mid- and lower backs. They originate in several places, including posterior aspects of the pelvis, the sacrum, lumbar and lower thoracic vertebrae, and the posterior surfaces of the lower three ribs. Interestingly enough, even with all of these origin points, the lats insert into one spot on the medial side of the upper humerus (6).

With this wide variety of origins, the lats can perform multiple functions. However, the lats are pretty weak in some of their extra roles and primarily function as shoulder extensors, adductors, and horizontal abductors (or horizontal extensors, depending on where you’re from) (6). The lats can also internally rotate the shoulder, however, they’re one of the weaker muscles that perform that function; the pecs have a much greater ability to perform internal rotation (6). Lastly, the lats can also somewhat help extend the lower back and rotate the torso, but they are pretty weak at these actions and don’t contribute a ton (6).

With this wide variety of origins, the lats can perform multiple functions. However, the lats are pretty weak in some of their extra roles and primarily function as shoulder extensors, adductors, and horizontal abductors (or horizontal extensors, depending on where you’re from) (6). The lats can also internally rotate the shoulder, however, they’re one of the weaker muscles that perform that function; the pecs have a much greater ability to perform internal rotation (6). Lastly, the lats can also somewhat help extend the lower back and rotate the torso, but they are pretty weak at these actions and don’t contribute a ton (6).

Most bodybuilders know that the lats can be divided into at least two (15), but probably more like three (1) sections. We have found these unique sections through EMG data (15) and mechanical modeling of the lats – researchers have uncovered three unique internal moments at a variety of shoulder angles (1) which suggests that each section of the lats might play a unique role in certain exercise variations. Regardless, we still train the lats with pulling exercises, like pull-ups, pulldowns, rows, and any variation of the aforementioned.

Bench Press Anatomy and Mechanics

Again, I think most bodybuilders have a pretty good idea of what the bench press is all about. The bench press is typically used to train the pectorals, deltoids, and triceps (2,16) – our pushing muscles, collectively. The primary joint actions that occur in a bench press are shoulder flexion, shoulder horizontal adduction, and elbow extension. Both the pecs and anterior delts can perform shoulder flexion and horizontal adduction with varying degrees of internal moments for each muscle in each action throughout the range of motion. And, last but not least, the triceps extend the elbow.

Okay, so, what gives? A bench press pretty much sounds like the opposite of what the lats do. So, why do people rag on about the importance of the lats in the bench press?

Something Sounds a Bit… Off

Using your lats in the bench press mostly stemmed from the powerlifting community – especially geared powerlifting. For those who aren’t familiar with powerlifting, there’s essentially (a bit of a simplification) two classes of powerlifting – raw and equipped. Raw powerlifting is just knee sleeves (or wraps in some cases), a belt, and wrist wraps (elbow sleeves sometimes, too). Equipped powerlifting, on the other hand, is all of that plus squat suits, bench shirts, and deadlift suits. These suits/shirts are composed of ridiculously strong and elastic materials that store a massive stretch during the eccentric portion of a lift and then rebound during the concentric to help lifters hoist more weight. This is why we see suits/shirts help out more in the squat and bench than the deadlift – there’s not much eccentric to build up tension in a deadlift suit during the lift, but there’s a few ways people can somewhat work around that.

For a quick example, Julius Maddox currently holds the raw (no weight class) bench press world record at 744lbs. The equipped (no weight class) bench press record, however, stands at a whopping 1105lbs, performed by Will Barotti. For comparison, strongman Benedikt Magnusson holds the raw world record deadlift at 1015lbs whereas Thor Bjornsson recently deadlifted 1105lbs in a deadlift suit to break the previous 1102lbs world record held by Eddie Hall. So, we have a nearly 50% difference in bench press world record, but only about a 10% difference in deadlift world records. A bit away from the point of this article, but you get the idea. For all intents and purposes, a bodybuilder would train more similarly to a raw powerlifter – this will be more important in the next section.

Anywho, equipped powerlifters in the late 90s and early 2000s starting harping on the lats in the bench press big time. Greg Nuckols’ theory is that it requires a substantial amount of lat strength to actually lower the bar to your chest in a bench shirt (14). If you’ve ever seen someone bench with a bench shirt, you’ll know it’s like watching paint dry while they lower the weight. You have to groove it just right to get the most out of a shirt, and the lats probably play a decent role in helping perfect that motion.

Therefore, anyone who’s read articles from equipped powerlifting coaches, like Dave Tate or Louie Simmons, has probably been doing a ton of lat work to try to improve their bench press. Does this really translate to a raw bench press, though?

Lats in the Bench Press

In a [raw] bench press, we want the shoulders to flex and horizontally adduct. The lats extend and horizontally abduct the shoulder. So… how can they play a role?

This theory has one primary thought that’s been tossed around a few times. Essentially, the idea is that, as you extend your shoulder into hyperextension (elbow past the midline of the body), the lats can actually turn into a shoulder flexor. How is this the case? Well, as the upper arm extends past the midline of the body, the attachment of the lat gets closer to its many origins. At some point, the attachment point could actually be behind the origin points. In this instance, if the lats were to contract further, they would actually flex the shoulder since they would be pulling the insertion towards the origin.

Now, whether or not that actually happens in a bench press is kind of a toss-up. Do we actually extend our shoulders enough to reach that point? If so, does that tiny little point actually play a large role in pressing? In short, I’m quite confident that the answer to both of those questions is, “No.”

We do achieve a decent bit of shoulder hyperextension in a bench press, and the degree of hyperextension can be influenced by grip width (7). However, mechanical analysis of the lats shows that the lats still act as shoulder extensors with the arms at the sides (1,10). While analysis of hyperextension wasn’t performed in those particular studies, it’s tough to imagine that the lats experience a rate of decline large enough to “flip” actions in slight shoulder hyperextension.

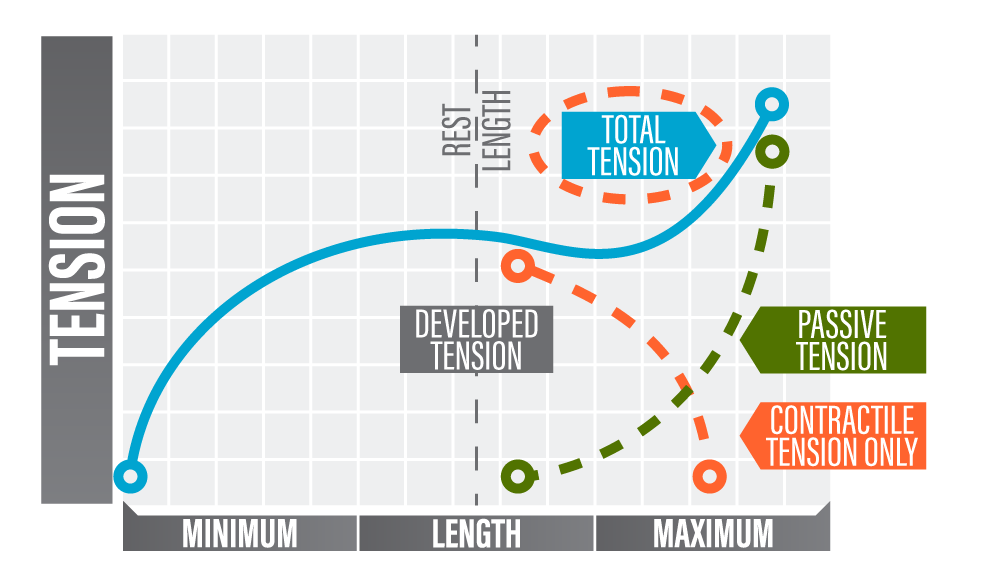

In addition, if the lats truly did become shoulder flexors at the bottom of a bench, would they even help much? One law that dictates how well muscles can produce force is the length-tension curve (11). This curve is essentially a bell-shaped curve when assessing active/contractile muscle components (i.e. contractile proteins). A muscle produces its highest active (contractile) force somewhere in the middle of its range of motion, and then active force drops off at both shorter and longer lengths. When the lats are in a position in which they might be able to flex the shoulder, they’d be at their shortest length possible. Therefore, they’d produce a very small amount of force that, frankly, I’m pretty sure is inconsequential to the execution of a bench press.

In addition, if the lats truly did become shoulder flexors at the bottom of a bench, would they even help much? One law that dictates how well muscles can produce force is the length-tension curve (11). This curve is essentially a bell-shaped curve when assessing active/contractile muscle components (i.e. contractile proteins). A muscle produces its highest active (contractile) force somewhere in the middle of its range of motion, and then active force drops off at both shorter and longer lengths. When the lats are in a position in which they might be able to flex the shoulder, they’d be at their shortest length possible. Therefore, they’d produce a very small amount of force that, frankly, I’m pretty sure is inconsequential to the execution of a bench press.

On the same vein, observationally, we probably achieve a similar degree of shoulder hyperextension in things like seated rows or chest-supported rows when compared to a bench press. If the lats truly switched into functional shoulder flexors, we’d certainly notice it on these row variations. While the theory makes sense at face value, I’m just not at all convinced that the lats can actually become functional shoulder flexors at a specific degree of hyperextension – they may be in a position to perform flexion, but they’d produce so little force that it wouldn’t matter.

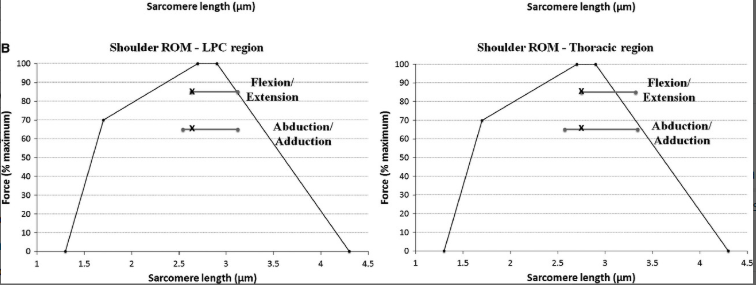

This hypothesis is at least somewhat confirmed by Gerling and Brown (2013) and their intense biomechanical research with the lat muscle. They found that the lats primarily act on the descending portion of the length-tension curve, meaning that they are mostly active in the flexion range of motion, i.e. hands at your side to hands over head. However, their analysis of the lats shows that the lats do not contract to lengths shorter than anatomical neutral (hands at sides). This denotes that the lats mostly produce force in this length range with their neutral (hands at side) position being just above 2.5 micrometers per sarcomere (tiny contractile unit of muscle). The posterior deltoid is probably the primary muscle tasked with hyperextending the shoulder (8). With this in mind, it’s tough to imagine the lats ever being able to flex the shoulder.

This hypothesis is at least somewhat confirmed by Gerling and Brown (2013) and their intense biomechanical research with the lat muscle. They found that the lats primarily act on the descending portion of the length-tension curve, meaning that they are mostly active in the flexion range of motion, i.e. hands at your side to hands over head. However, their analysis of the lats shows that the lats do not contract to lengths shorter than anatomical neutral (hands at sides). This denotes that the lats mostly produce force in this length range with their neutral (hands at side) position being just above 2.5 micrometers per sarcomere (tiny contractile unit of muscle). The posterior deltoid is probably the primary muscle tasked with hyperextending the shoulder (8). With this in mind, it’s tough to imagine the lats ever being able to flex the shoulder.

Another reason raw benchers might train their lats would be to improve the unracking of the bar before starting the press. In theory, this would certainly seem plausible since this motion is largely reliant on shoulder extension. However, biomechanical analysis shows that the lower portion of the pecs actually have a pretty similar internal moment for shoulder extension above 90-degrees of flexion when compared to the lats (1). In fact, the lats’ peak shoulder extension moment occurs around 40-degrees of flexion (1) – well past the unracking point in the bench press. We see this driven home in studies showing that the pecs are actually more active in a dumbbell pullover exercise than the lats (5). So, realistically, the lower pecs are at least just as important for unracking the bar, but people still might feel their lats… or do they?

The last theory I’ve been mulling over with the lats and the bench press is that people might simply be mistaking their serratus anterior muscle for their lats. I often see a similar conundrum with people thinking their hamstrings are sore after squats, when it’s really their adductors (more info in our article here). The serratus anterior is the muscle that’s situated between your ribs and shoulder blades and is mostly responsible for protraction and upward rotation of the shoulder blade (13). Whenever you do a lat spread pose, you’re actually contracting your serratus to “spread” the lats. Many people end up mistaking these muscles for being one and the same, but they certainly are not.

While neither protraction or upward rotation will happen to a large degree in a properly-performed flat bench press, the serratus is the muscle that provides the “foundation” for shoulder flexion (13). In addition, slight protraction will certainly occur during the unracking motion – hence why people probably feel their “lats” in this action. Multiple studies have found significant serratus activation in the bench press (4,17) whereas other studies show minimal lat activation in the bench press (2,5). When I say minimal, I mean that the pecs are ten times as active as the lats in the bench press. This was first reported in 1995 by Barnett et al. and was repeated 23 years later by Borges et al. in 2018. It’s pretty rare to see data be repeated so similarly between studies that were published 23-years apart. I think we can accept that the lats are minimally active in a bench press, and that the serratus probably plays a more significant role, even if primarily through stabilization.

Takeaways and Conclusion

Ultimately, I don’t think the lats play much of a role in the bench press. Sure, they probably help stabilize the shoulder a bit, but they’re not nearly as important as the pecs, shoulders, or triceps – or even serratus, for that matter. Now, I don’t want people to think that means that lat training is pointless for developing a big bench. Muscle imbalances between anterior (pec and deltoid) and posterior (lats, etc.) shoulder muscles are still one of the most common causes of shoulder injuries in athletes (3,12). You can’t develop a big bench if injuries are constantly cutting your pressing days short. With this in mind, I still recommend that people with big bench aspirations perform at least as much pulling volume as pushing volume. Other professionals, like Matt Wenning, often recommend a 2:1 ratio of pulling to pushing volume for optimal shoulder health.

Ultimately, I don’t think the lats play much of a role in the bench press. Sure, they probably help stabilize the shoulder a bit, but they’re not nearly as important as the pecs, shoulders, or triceps – or even serratus, for that matter. Now, I don’t want people to think that means that lat training is pointless for developing a big bench. Muscle imbalances between anterior (pec and deltoid) and posterior (lats, etc.) shoulder muscles are still one of the most common causes of shoulder injuries in athletes (3,12). You can’t develop a big bench if injuries are constantly cutting your pressing days short. With this in mind, I still recommend that people with big bench aspirations perform at least as much pulling volume as pushing volume. Other professionals, like Matt Wenning, often recommend a 2:1 ratio of pulling to pushing volume for optimal shoulder health.

All-in-all, keep training your back! While I don’t think lat training is going to directly boost your bench press, any improvements or maintenance of shoulder health should help you continue training with minimal injuries. It takes a long time to develop a monster press, and staying healthy throughout your training career is the most important step you can take to reach a multi-plate milestone on bench.

As a brief conclusion, we have three main criteria we seek to satisfy when confirming whether or not a muscle is involved in an exercise:

- Does the muscle’s function(s) align with the joint actions performed in the exercise?

- Does mechanical modeling show that the muscle significantly contributes to the joint actions in an exercise?

- Does EMG data show that the muscle is significantly active during an exercise?

The lats fail all three for the bench press.

References

- Ackland, D. C., Pak, P., Richardson, M., & Pandy, M. G. (2008). Moment arms of the muscles crossing the anatomical shoulder. Journal of Anatomy, 213(4), 383-390.

- Barnett, C., Kippers, V., & Turner, P. (1995). Effects of variations of the bench press exercise on the EMG activity of five shoulder muscles. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 9(4), 222-227.

- Bell-Jenje, T. (2005). Incidence, nature and risk factors in shoulder injuries of national academy cricket players over 5 years-a retrospective study. South African Journal of Sports Medicine, 17(4), 1-7.

- Borges, E., Dalla, H., Mastandrea, L., Nunes, S., & Santarem, J. (2019). Comparative evaluation of muscular activation and scapular kinematics in a chest press lever machine and a barbell bench press. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 19, 912-916.

- Borges, E., Mezêncio, B., Pinho, J., Soncin, R., Barbosa, J., Araujo, F., … & Serrão, J. (2018). Resistance training acute session: pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi and triceps brachii electromyographic activity. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 18(2), 648-653.

- Gerling, M. E., & Brown, S. H. (2013). Architectural analysis and predicted functional capability of the human latissimus dorsi muscle. Journal of Anatomy, 223(2), 112-122.

- Gomo, O., & Van Den Tillaar, R. (2016). The effects of grip width on sticking region in bench press. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(3), 232-238.

- Hik, F., & Ackland, D. C. (2019). The moment arms of the muscles spanning the glenohumeral joint: a systematic review. Journal of Anatomy, 234(1), 1-15.

- Kholinne, E., Zulkarnain, R. F., Sun, Y. C., Lim, S., Chun, J. M., & Jeon, I. H. (2018). The different role of each head of the triceps brachii muscle in elbow extension. Acta Orthopaedica et Traumatologica Turcica, 52(3), 201-205.

- Kuechle, D. K., Newman, S. R., Itoi, E., Morrey, B. F., & An, K. N. (1997). Shoulder muscle moment arms during horizontal flexion and elevation. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 6(5), 429-439.

- Lieber, R. L. (2018). Biomechanical response of skeletal muscle to eccentric contractions. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 7(3), 294-309.

- Miller, A. H., Evans, K., Adams, R., Waddington, G., & Witchalls, J. (2018). Shoulder injury in water polo: a systematic review of incidence and intrinsic risk factors. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 21(4), 368-377.

- Neumann, D. A., & Camargo, P. R. (2019). Kinesiologic considerations for targeting activation of scapulothoracic muscles-part 1: serratus anterior. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 23(6), 459-466.

- Nuckols, G. (2016). The lats in the bench press: much ado about very little. Retrieved from: https://www.strongerbyscience.com/lats-bench-press-much-ado-little/

- Paton, M. E., & Brown, J. M. (1995). Functional differentiation within latissimus dorsi. Electromyography and clinical neurophysiology, 35(5), 301-309.

- Schick, E. E., Coburn, J. W., Brown, L. E., Judelson, D. A., Khamoui, A. V., Tran, T. T., & Uribe, B. P. (2010). A comparison of muscle activation between a Smith machine and free weight bench press. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(3), 779-784.

- Torres Piraua, A. L., Barros Beltrão, N., Ximenes Santos, C., Rodarti Pitangui, A. C., & Cappato de Araújo, R. (2017). Analysis of muscle activity during the bench press exercise performed with the pre-activation method on stable and unstable surfaces. Kinesiology: International Journal of Fundamental and Applied Kinesiology, 49(2.), 161-168.

From being a mediocre athlete, to professional powerlifter and strength coach, and now to researcher and writer, Charlie combines education and experience in the effort to help Bridge the Gap Between Science and Application. Charlie performs double duty by being the Content Manager for The Muscle PhD as well as the Director of Human Performance at the Applied Science and Performance Institute in Tampa, FL. To appease the nerds, Charlie is a PhD candidate in Human Performance with a master’s degree in Kinesiology and a bachelor’s degree in Exercise Science. For more alphabet soup, Charlie is also a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist (ACSM-EP), and a USA Weightlifting-certified performance coach (USAW).