Introduction

Let’s temper expectations quick: we’re not delivering as theatrical a piece as the Godzilla-esque title would suggest. Rather, the primary goals of this article are to A) clearly define the difference(s) between bodybuilding and powerlifting and B) determine how those differences [should] affect training or nutrition plans for each sport. And, let’s be honest, neither one is really a sport, but we don’t need to go down that route today.

Since the majority of our content is geared simultaneously at bodybuilders and powerlifters, it’s worth discussing some of the unique disparities between training and nutrition plans for bodybuilding and powerlifting. Let’s get cracking.

What is Bodybuilding?

There’s probably some oddly worded Google definition for bodybuilding that I, frankly, have no interest in searching for. In its simplest form, bodybuilding is simply the act of building one’s body through a regimented training and nutrition program. I think the “regimented” portion of this definition helps separate bodybuilding from general fitness; most gym goers would be quick to say they’re not bodybuilders, and many bodybuilders would be pretty offended if you lumped them in with the average gym goer. “It’s different, BRO!”

There’s probably some oddly worded Google definition for bodybuilding that I, frankly, have no interest in searching for. In its simplest form, bodybuilding is simply the act of building one’s body through a regimented training and nutrition program. I think the “regimented” portion of this definition helps separate bodybuilding from general fitness; most gym goers would be quick to say they’re not bodybuilders, and many bodybuilders would be pretty offended if you lumped them in with the average gym goer. “It’s different, BRO!”

Competitive bodybuilding takes it a step further. Competitive bodybuilding involves building your body, incinerating every ounce of body fat you possible can, then stepping on a stage to compete against other competitive bodybuilders. All of you are mostly naked and caked in spray tan and body oil. Totally not weird, right? Every bodybuilding competition requires a set list of poses alongside other competitors, but many competitions also have you perform a short (60 seconds or so) solo routine. It depends on which category you’re in, but usually, the most jacked and ripped competitor wins. Symmetry also plays a large role, but many folks will tell you that the 80s and 90s were more so about symmetry whereas today’s bodybuilding is all about that mass.

To many, competitive bodybuilding is the upper echelon of physique sports. The penultimate human form. In a bodybuilding competition, each competitor should be the most jacked and leanest they’ve ever been and, thus, specific training and nutrition approaches need to be taken to achieve this peak. Ultimately, the chasm between bodybuilding and competitive bodybuilding raises the question – are you actually a bodybuilder if you’ve never competed? While philosophizing over such teeth-grinding topics is outside the scope of this piece, there certainly is a difference between the two.

What is Powerlifting?

Powerlifting is quite a bit easier to define. Essentially, powerlifting is a competition in which competitors battle it out to see who can squat, bench press, and deadlift the most. While individual victories in each category are pretty cool, your highest weights achieved on each lift are summed to create your “total.” If you’ve ever stumbled across a mid-tier level powerlifter’s Instagram account, odds are they have their total in their bio. Heck, it might even be part of their username. Tells you a lot about powerlifting, doesn’t it?

Powerlifting is quite a bit easier to define. Essentially, powerlifting is a competition in which competitors battle it out to see who can squat, bench press, and deadlift the most. While individual victories in each category are pretty cool, your highest weights achieved on each lift are summed to create your “total.” If you’ve ever stumbled across a mid-tier level powerlifter’s Instagram account, odds are they have their total in their bio. Heck, it might even be part of their username. Tells you a lot about powerlifting, doesn’t it?

In short, a powerlifting competition involves the squat, bench, and deadlift – in that order. Every competitor gets three attempts at each lift – four attempts if you’re trying to break some sort of record on your fourth. Every lift is judged by three judges and for a lift to be successful, at least two of the judges have to “white light” your lift. The most important aspects are that a squat has to break parallel, a bench has to pause on your chest, and a deadlift must be fully locked out. Missing any of those components almost always results in red lights.

Now, the above definition assumes that, for one to be a powerlifter, they need to strap up in a singlet and actually compete. This is a similar chasm to bodybuilding, but I think the powerlifting one is a little more straight forward. Powerlifting isn’t nearly as popular a hobby as bodybuilding and most people who “do” powerlifting have either competed in the past or are planning to compete in the future. Alas, we could argue all day about these mostly pointless distinctions, so let’s forge ahead.

It’s worth discussing that powerlifting has [at least] two unique classes: geared and raw. Recently, there’s been a push to separate raw from raw + wraps, but that’s really not worth discussing here. Regardless, geared powerlifting involves squat suits, bench shirts, and deadlift suits whereas raw powerlifting has none of that – only a belt, knee wraps (or sleeves), and wrist wraps are allowed. Some federations will also allow elbow sleeves. Geared powerlifting is where we see monstrous squat and bench numbers, but deadlift suits don’t help out as much since there’s no eccentric component in a deadlift. Therefore, a geared powerlifter almost always out-squats their deadlift, and occasionally out-benches their deadlift as well. On the flip side, a raw powerlifter usually deadlifts more than they squat, and almost certainly benches less than their squat or deadlift. At least we hope…

Ultimately, the primary difference between bodybuilding and powerlifting is that, in a bodybuilding competition, you look your best. However, in a powerlifting meet, you perform your best. Therefore, it’s worth going over some common training variables and how they might differ between bodybuilders and powerlifters.

Training Differences

Rep Ranges

This is one area where powerlifting and bodybuilding differ. While the majority of bodybuilders usually train in the 8-12 rep range, research shows that using anywhere from 3-30 reps can boost growth as long as you train close to failure (Schoenfeld et al., 2017). Additionally, there might be some benefit to rotating rep ranges, especially in advanced bodybuilders (Simao et al., 2012). Regardless, when it comes to boosting growth, the 8-12 rep range is probably the best middle ground for maximizing tension (heavy enough weight) while also promoting some metabolic stress (burn/pump). The combination of tension and metabolic stress should be the perfect recipe for stacking on slabs of muscle.

On the flip side, powerlifters generally train their competitive lifts in the 2-5 rep range. This range is more specific to competing, since a competition only tests a single rep at a time. Additionally, research has shown this range to be more effective at developing strength (Campos et al., 2002). However, it’s important to bear in mind that powerlifters also use the 8-12 rep range on a good portion of their accessory work, especially if they’re not close to a competition.

Overall, the rep ranges used for bodybuilding and powerlifting aren’t that different. Many modern powerlifters almost train more like bodybuilders in the offseason anyways – and for good reason, as research shows there’s a strong correlation between muscle size and strength (Akagi et al., 2014). If you’re a powerlifter, odds are, you’ll train the big three (squat, bench, and deadlift) in the lower rep ranges more often. Moreover, you’ll usually perform more sets to A) still achieve a sufficient level of volume and B) perform more “first” reps, since those are more specific to powerlifting than any other rep.

Rest Periods

Ah, yes. There are tons of memes online poking fun at the rest periods utilized by powerlifters. However, these rest periods are at least somewhat rooted in science, as research has shown that longer rest periods are better for promoting strength gains than short rest periods (Grgic et al., 2018). This is likely due to the greater accumulation of central and peripheral fatigue from using short rest periods – this combination isn’t optimal for building strength.

Ah, yes. There are tons of memes online poking fun at the rest periods utilized by powerlifters. However, these rest periods are at least somewhat rooted in science, as research has shown that longer rest periods are better for promoting strength gains than short rest periods (Grgic et al., 2018). This is likely due to the greater accumulation of central and peripheral fatigue from using short rest periods – this combination isn’t optimal for building strength.

Conversely, bodybuilders should use a variety of rest period lengths in their training. Research shows us that 3-minute-long rest periods are generally the most effective for building muscle (Schoenfeld et al., 2016), however, there is the occasional use for shorter rest periods. Using shorter rests, like 30-60-seconds, maximizes metabolic stress during training. If you’re looking to really chase the pump/burn in a workout, keeping rest periods short can certainly help. While this might not be the most effective stimulus for growth (Wackerhage et al., 2019), it can be useful for a deload period or simply adding variation to your training.

Overall, rest periods between bodybuilding and powerlifting are probably going to differ quite a bit. Powerlifters want to minimize fatigue between sets to ensure there’s no interference with the heavy weights they’re pushing. Contrarily, bodybuilders do have the occasional use for shorter rest periods, especially during isolation exercises that don’t impose a large interset recovery tax.

Exercise Selection

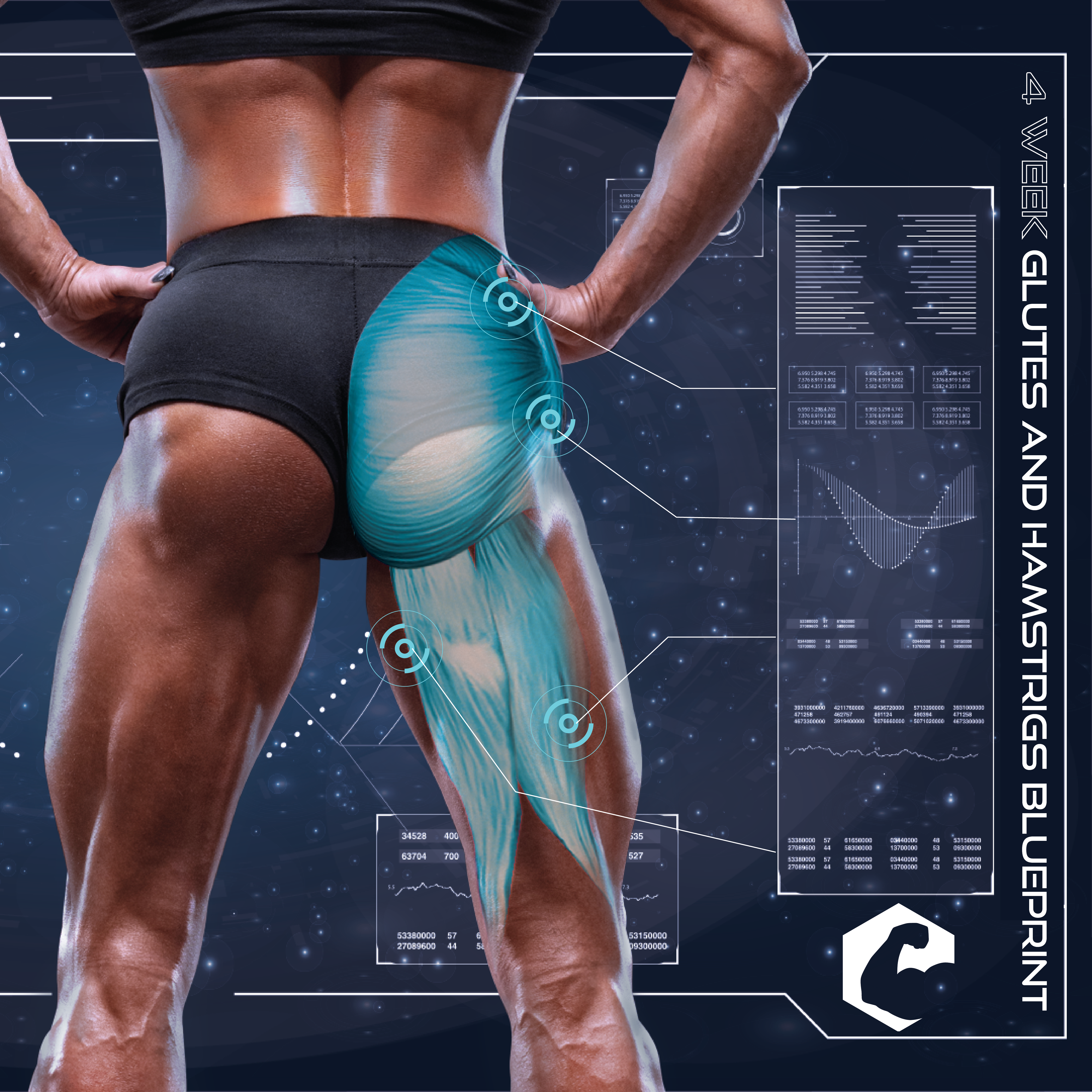

For both powerlifters and bodybuilders, exercise selection is largely up to individual goals and needs. A bodybuilder is going to use a good amount of compound movements; however, research shows that compound movements don’t fully develop every muscle involved in them (Brandao et al., 2020; Clark et al., 2012). Therefore, isolation movements are going to be used quite a bit in bodybuilding to ensure that a physique is perfectly crafted and symmetrical.

Powerlifting, on the other hand, can be a little more strict. You pretty much have to perform the big three with at least some sort of consistency if you want to be a good powerlifter. You need to be super proficient in the squat, bench press, and deadlift so that they are second nature on competition day. Outside of this necessity, powerlifters often select “direct” accessory exercises that are designed to build one of the big three lifts. A lifter using good mornings to build their squat is a great example.

For both powerlifters and bodybuilders, accessory or isolation exercises are going to be used to target weak points. However, the definition of weak point differs between the groups. A bodybuilder uses accessory exercises to build up “lagging” muscles groups – i.e., muscle groups that aren’t developing as well as others. Just about everyone has body parts that don’t grow as well as other ones; therefore, you need to implement specific exercises to make sure no muscle group gets left behind.

On the other hand, powerlifters use accessory exercises to boost “weaknesses” in certain movements. Let’s say you notice you’re having trouble locking out your bench press. In this case, you’d implement things like floor presses, board presses, or even Spoto presses to work on your lockout strength. Essentially, you’re building whatever weak link is keeping you from performing your best on the big three.

Internal vs External Focus

It is well-known that bodybuilders are often told to train with the “mind-muscle connection.” That is, essentially, a form of internal focus in which an individual is emphasizing the muscle contraction involved in a given movement. Research has consistently shown that this method does increase muscle activation (Calatayud et al., 2017; Marchant et al., 2009) but it has one primary drawback. Research has also shown that using an internal focus can result in lower strength and power compared to using an external focus (Becker et al., 2015; Marchant et al., 2009).

With this in mind, powerlifters are often told to do the exact opposite – adopt an external focus during lifting. An external focus primarily utilizes external cues – for instance, you might tell a bodybuilder to focus on their glutes or quads in a squat – an internal focus, right? However, for a powerlifter, you’d tell them to “push the floor away” – an external focus.

While long-term adaptations between types of focus haven’t really been explored, it’s probably a smart idea for bodybuilders to utilize an internal focus and improve their mind-muscle connection, especially if they plan on competing. On the flip side, powerlifters should definitely use cues that promote an external focus. Some examples for the bench and deadlift are:

(Bench): Push yourself away from the bar.

(Deadlift): Keep the bar close to your hips.

Cardio

Yep, bring on more of the internet memes making fun of powerlifters not doing any cardio. While hilarious, this is at least somewhat for good reason. Doing too much cardio probably interferes with strength adaptations more than size (Ellefsen & Baar, 2019; Hakkinen et al., 2003) due to the lasting central and peripheral fatigue that cardio can impose. With this in mind, there are obviously differences in cardio training for both groups.

Yep, bring on more of the internet memes making fun of powerlifters not doing any cardio. While hilarious, this is at least somewhat for good reason. Doing too much cardio probably interferes with strength adaptations more than size (Ellefsen & Baar, 2019; Hakkinen et al., 2003) due to the lasting central and peripheral fatigue that cardio can impose. With this in mind, there are obviously differences in cardio training for both groups.

Bodybuilders often associate cardio with a cutting period, however, cardio really isn’t any more effective at burning calories than lifting weights (Greer et al., 2015; Kirk et al., 2009). If anything, adding cardio to your program while mostly maintaining strength training volume will certainly boost overall calorie expenditure. However, dropping lifting workouts and replacing them with more cardio will probably do little for fat burning.

We often hear the argument that steady state cardio places us in the “fat burning zone” in which we’re relying on fat for fuel. While it’s certainly true that fat burning is maximized around 45-65% maximal intensity (Purdom et al., 2018), the amount of total energy you’re using at this rate is so low it’s almost inconsequential to overall fat loss when compared to other forms of exercise. A recent meta-analysis concluded that interval training is more effective for overall fat loss than traditional cardio (Viana et al., 2019) and, intriguingly, interval training doesn’t take nearly as long, nor does it require you to spend extended time in the “fat burning zone.”

Therefore, while bodybuilders often use traditional cardio for fat loss, this practice is probably a little outdated. Some bodybuilders might toss in cardio here or there for health benefits, but let’s be honest, that’s probably an overwhelming minority among younger bodybuilders.

When it comes to cardio for powerlifting, the common credo is something along the lines of, “have enough work capacity to survive and recover from training, but that’s it.” Indeed, powerlifting has literally no endurance component whatsoever. However, we generally associate better cardio/work capacity with improved recovery – not only between sets (McLester et al., 2008), but also between workouts (Kilpelänaho, 2012). With this in mind, many powerlifters use things like sleds, weighted carries, and other forms of “loaded” cardio that are still sort of specific to powerlifting and not as boring as traditional cardio. That’s certainly not to say that bodybuilders can’t do loaded cardio too, however, it just seems much more prevalent in the powerlifting field.

While powerlifting and bodybuilding certainly differ in a few more areas (training frequency, periodization schemes, etc.), we’ll skip those for now so we can move forward to a discussion on some nutrition differences. Who knows, maybe we’ll make a Part 2 for this piece that covers those last bits in more detail.

Nutrition Differences

One of the biggest differences between bodybuilding and powerlifting is the pursuit of an optimal physique versus the quest for a massive total. Therefore, nutrition practices are occasionally a little different between bodybuilders and powerlifters. However, it’s important to keep in mind that the majority of powerlifting is actually weight class-constrained – sure, we always see the massive fellas hoisting insane weights in the superheavyweight class, but that’s only one or two weight classes in powerlifting. Most other lifters do end up doing some sort of cut to make weight for their class and usually stay relatively lean in the offseason.

With this in mind, let’s get into some of the major nutrition differences that are generally prevalent (or should be) between bodybuilders and powerlifters.

Total Calorie Intake

Many people will point towards this being the main difference between bodybuilding and powerlifting – and might even reference the famous bulking diet employed by legendary powerlifters JM Blakley and Dave Tate here. In my early powerlifting days, I definitely fell into this trap – my daily diet of donuts, chocolate milk, frozen pizza, Panda Express, and more chocolate milk certainly helped me put on some weight and get stronger. But was it necessary?

Many people will point towards this being the main difference between bodybuilding and powerlifting – and might even reference the famous bulking diet employed by legendary powerlifters JM Blakley and Dave Tate here. In my early powerlifting days, I definitely fell into this trap – my daily diet of donuts, chocolate milk, frozen pizza, Panda Express, and more chocolate milk certainly helped me put on some weight and get stronger. But was it necessary?

Outside the world of superheavyweight powerlifting, I don’t think calorie intake is going to be crazy different between bodybuilders and powerlifters. Certainly, at the highest level of each sport, a bodybuilding diet is probably “cleaner,” but the biggest bodybuilders are still crushing thousands of calories a day – check out an example of a Ronnie Coleman diet here or a sample Jay Cutler diet here. This calorie surplus is needed to support muscle building and strength gains – especially at the highest level in each sport where, ahem, “medicines” are aiding recovery and gains.

At the end of the day, both powerlifters and bodybuilders are going to consume a calorie surplus during the offseason. The source of that surplus might differ a bit between camps since powerlifters [usually] aren’t as obsessively concerned with body composition as bodybuilders. Eventually, however, most powerlifters will need to cut weight for a meet and bodybuilders will certainly need to cut if they plan on dazzling on the stage or beach. A bodybuilding cut is likely going to be more strict as many powerlifters shoot for more of a water cut than actual fat cut (Gee et al., 2020). Heck, I’ve seen top level powerlifters cut 30lbs of water in just a few days to make weight for a meet – and then gain most of it back overnight before the actual competition. Again, various “supplements” certainly hasten the progress of such a water cut, but those are wayyyyy outside the scope of this piece.

Regardless, cutting diets between bodybuilders and powerlifters might be similar at first, but bodybuilders will ultimately continue restricting calories whereas powerlifters will use a water cut for their home stretch. Water cutting isn’t uncommon in bodybuilding, especially in the higher levels, however, it’s more often used for aesthetic purposes (coming in dry/peeled) than making weight (Chappell & Simper, 2018; Roberts et al., 2020). Unless, of course, you’re in a specific bodybuilding weight class, too. Good lord this keeps evolving, huh?

Before we get too deep into water cuts, let’s just move ahead to other nutrition habits. Otherwise, we’ll be here all day and that’s a rabbit hole I’m not interested in diving down.

Macronutrient Splits

This section will be pretty concise; I’m not convinced of any massive difference between macro splits when comparing bodybuilders to powerlifters. Obviously, the heaviest powerlifters probably get a little wayward with their carb and fat intake (have to maintain 350lbs somehow, right?), but I’d guess that most bodybuilders and powerlifters generally consume a high protein diet with high/moderate carbs and low/moderate fat. This is for good reason; research has consistently shown that high protein diets are best for optimizing muscle mass (Jager et al., 2017), of which is highly important to both powerlifters and bodybuilders.

When it comes to cutting, bodybuilders usually have the choice of cutting carbs, fats, or a mix of both in order to achieve their calorie deficit. Since both approaches have been shown to lead to successful fat loss, it’s often up to the bodybuilder as to which route they want to take (Roberts et al., 2020). A similar option exists in powerlifting, however, calorie and/or macro restriction can certainly impair performance (Moore et al., 2019), so careful planning is necessary. Some might recommend powerlifters cut carbs a bit more to maintain fat intake and, thus, joint and hormone health (Helms et al., 2014), however, cutting carbs too sharply could interfere with workout performance and recovery. By the time you’re cutting carbs to such a level, though, your training will have tapered down to a more manageable level. Something to consider when you’re planning on a cut as a powerlifter.

Irrespective of training discipline, both groups should aim for a high protein intake year-round, but especially during a cutting period where maintaining lean mass is of even higher importance (Roberts et al., 2020). You can’t look good on stage without any muscle, and you can’t hoist a new personal record if your muscles have wasted away from your diet.

Meal Timing

Specific timing of meals has kind of phased out in the bodybuilding world. I don’t think it was ever as strict in powerlifting, but both camps generally recommended some sort of post-workout meal. While this practice is probably more important for those performing fasted training, it’s still a decent idea to get in some sort of protein and carbs following your workout. You might as well take advantage of the protein synthesis spike and tissue sensitivity during this period and eating in this period would never impair gains, either.

Specific timing of meals has kind of phased out in the bodybuilding world. I don’t think it was ever as strict in powerlifting, but both camps generally recommended some sort of post-workout meal. While this practice is probably more important for those performing fasted training, it’s still a decent idea to get in some sort of protein and carbs following your workout. You might as well take advantage of the protein synthesis spike and tissue sensitivity during this period and eating in this period would never impair gains, either.

Additionally, meal frequency has mostly fallen out of favor in both camps, too. I remember reading bodybuilding magazines in the early 2000s that always recommended “keeping your metabolism stoked” by eating several small meals throughout the day. Unfortunately, this recommendation was based on a single study from the 80s, of which no one has been able to recreate since (Schoenfeld et al., 2015). Regardless, a regular eating schedule (~3hr between meals) should benefit both powerlifters and bodybuilders as this practice is likely optimal for maintaining protein synthesis throughout the day (Moore et al., 2012).

Lastly, both groups would also benefit from consuming some sort of protein source before hitting the hay. Studies have shown that protein ingestion before bed increases protein synthesis overnight (Trommelen & Van Loon, 2016). The general recommendation is to consume a slower digesting protein, either casein or a full meal, as whey might be too rapidly digesting for your 7-hour+ snooze. Some bodybuilders might be uncomfortable with consuming an entire meal before bed due to the long-held belief that nighttime snacking leads to fat gain. As long as your meal isn’t absolute garbage that overshoots your target calorie intake, you should be fine.

Conclusion

Ultimately, we’re not really sure if this is more of a “how to” guide or more like a “this versus that” piece. It evolved a bit as we wrote it, so maybe it can serve as both? I don’t know, and I don’t think it matters much. If anything, we hopefully succeeded in our goal of covering some of the primary differences between bodybuilding and powerlifting and how those differences affect training and nutrition practices.

Some might simply assume most of this is common knowledge and, to a degree, we’d agree with that. However, for folks that are new to the field or the gym, it’s good knowledge to have moving forward, especially if you plan on interacting with either group on a consistent basis. And you’d be surprised at how many people there are in the science field that have minimal understanding of either bodybuilding or powerlifting. Getting the basics of each strength sport as well as the common practices of its participants definitely helps researchers better direct their efforts to help the strength community as a whole.

Easter Egg

This is another piece we’ll probably update as time goes on. I don’t think we’ll get any groundbreaking research that changes a training or nutrition practice to a large degree for either group, but there’s definitely stuff we left out that we can always add in at a later time.

References

- Akagi, R., Tohdoh, Y., Hirayama, K., & Kobayashi, Y. (2014). Relationship of pectoralis major muscle size with bench press and bench throw performances. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 28(6), 1778-1782.

- Becker, K. A., & Smith, P. J. (2015). Attentional focus effects in standing long jump performance: Influence of a broad and narrow internal focus. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29(7), 1780-1783.

- Brandão, L., de Salles Painelli, V., Lasevicius, T., Silva-Batista, C., Brendon, H., Schoenfeld, B. J., … & Teixeira, E. L. (2020). Varying the order of combinations of single-and multi-joint exercises differentially affects resistance training adaptations. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 34(5), 1254-1263.

- Calatayud, J., Vinstrup, J., Jakobsen, M. D., Sundstrup, E., Colado, J. C., & Andersen, L. L. (2017). Mind-muscle connection training principle: influence of muscle strength and training experience during a pushing movement. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(7), 1445-1452.

- Campos, G. E., Luecke, T. J., Wendeln, H. K., Toma, K., Hagerman, F. C., Murray, T. F., … & Staron, R. S. (2002). Muscular adaptations in response to three different resistance-training regimens: specificity of repetition maximum training zones. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 88(1), 50-60.

- Chappell, A. J., & Simper, T. N. (2018). Nutritional peak week and competition day strategies of competitive natural bodybuilders. Sports, 6(4), 126.

- Clark, D. R., Lambert, M. I., & Hunter, A. M. (2012). Muscle activation in the loaded free barbell squat: a brief review. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(4), 1169-1178.

- Ellefsen, S., & Baar, K. (2019). Proposed Mechanisms Underlying the Interference Effect. In Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training (pp. 89-97). Springer, Cham.

- Gee, T., Campbell, P., Bargh, M., & Martin, D. (2020, July). A comparison of rapid weight loss practices within regional, national and international powerlifters. National Strength and Conditioning Association 2020 National Conference.

- Greer, B. K., Sirithienthad, P., Moffatt, R. J., Marcello, R. T., & Panton, L. B. (2015). EPOC comparison between isocaloric bouts of steady-state aerobic, intermittent aerobic, and resistance training. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 86(2), 190-195.

- Grgic, J., Schoenfeld, B. J., Skrepnik, M., Davies, T. B., & Mikulic, P. (2018). Effects of rest interval duration in resistance training on measures of muscular strength: a systematic review. Sports Medicine, 48(1), 137-151.

- Häkkinen, K., Alen, M., Kraemer, W. J., Gorostiaga, E., Izquierdo, M., Rusko, H., … & Paavolainen, L. (2003). Neuromuscular adaptations during concurrent strength and endurance training versus strength training. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 89(1), 42-52.

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1), 1-20.

- Jäger, R., Kerksick, C. M., Campbell, B. I., Cribb, P. J., Wells, S. D., Skwiat, T. M., … & Antonio, J. (2017). International society of sports nutrition position stand: protein and exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1), 1-25.

- Kilpelänaho, E. M. (2012). Combined strength and endurance exercise induced fatigue and recovery. Master’s thesis. University of Jyväskylä.

- Kirk, E. P., Donnelly, J. E., Smith, B. K., Honas, J., LeCheminant, J. D., Bailey, B. W., … & Washburn, R. A. (2009). Minimal resistance training improves daily energy expenditure and fat oxidation. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 41(5), 1122.

- Marchant, D. C., Greig, M., & Scott, C. (2009). Attentional focusing instructions influence force production and muscular activity during isokinetic elbow flexions. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(8), 2358-2366.

- McLester, J. R., Green, J. M., Wickwire, P. J., & Crews, T. R. (2008). Relationship of VO2 peak, body fat percentage, and power output measured during repeated bouts of a Wingate protocol. International Journal of Exercise Science, 1(2), 5.

- Moore, D. R., Areta, J., Coffey, V. G., Stellingwerff, T., Phillips, S. M., Burke, L. M., … & Hawley, J. A. (2012). Daytime pattern of post-exercise protein intake affects whole-body protein turnover in resistance-trained males. Nutrition & Metabolism, 9(1), 1-5.

- Moore, J. L., Travis, S. K., Lee, M. L., & Stone, M. H. (2019). Making Weight: Maintaining Body Mass for Weight Class Barbell Athletes. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 41(6), 110-114.

- Purdom, T., Kravitz, L., Dokladny, K., & Mermier, C. (2018). Understanding the factors that affect maximal fat oxidation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 15(1), 1-10.

- Roberts, B. M., Helms, E. R., Trexler, E. T., & Fitschen, P. J. (2020). Nutritional recommendations for physique athletes. Journal of human kinetics, 71, 79.

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Aragon, A. A., & Krieger, J. W. (2015). Effects of Meal Frequency on Weight Loss and Body Composition: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrition Reviews, 73(2), 69-82.

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2017). Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low-vs. high-load resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(12), 3508-3523.

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Pope, Z. K., Benik, F. M., Hester, G. M., Sellers, J., Nooner, J. L., … & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Longer interset rest periods enhance muscle strength and hypertrophy in resistance-trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(7), 1805-1812.

- Simão, R., Spineti, J., de Salles, B. F., Matta, T., Fernandes, L., Fleck, S. J., … & Strom-Olsen, H. E. (2012). Comparison between nonlinear and linear periodized resistance training: hypertrophic and strength effects. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(5), 1389-1395.

- Wackerhage, H., Schoenfeld, B. J., Hamilton, D. L., Lehti, M., & Hulmi, J. J. (2019). Stimuli and sensors that initiate skeletal muscle hypertrophy following resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126(1), 30-43.

From being a mediocre athlete, to professional powerlifter and strength coach, and now to researcher and writer, Charlie combines education and experience in the effort to help Bridge the Gap Between Science and Application. Charlie performs double duty by being the Content Manager for The Muscle PhD as well as the Director of Human Performance at the Applied Science and Performance Institute in Tampa, FL. To appease the nerds, Charlie is a PhD candidate in Human Performance with a master’s degree in Kinesiology and a bachelor’s degree in Exercise Science. For more alphabet soup, Charlie is also a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist (ACSM-EP), and a USA Weightlifting-certified performance coach (USAW).