Introduction

“Periodization” is a term that’s often loosely tossed around with little context or purpose. In my experience in the strength and conditioning field, most coaches have little to no understanding of periodization theory, let alone how to apply these theories towards athlete training. There’s tons of information available about periodization, from textbooks, to theoretical frameworks, and even individual research studies. However, we’re mostly going to gloss over the nitty gritty as (you’ll see soon) it might not be that useful for bodybuilding.

The simplest definition of periodization is planned variation within a long-term training program. The main highlights are planned, variation, and long-term. We’ll get into that in a bit. Since periodization is 99% theory anyways, let’s discuss the history and application of periodization and then make some takeaways for fitness and bodybuilding.

Humble Beginnings

Scholars often credit the Soviet Union and their quest for Olympic dominance with the development of periodization. There are four main thoughts/occurrences that people typically link to the creation of periodization:

- Soviet athletes often trained in sport camps away from their homes. Soviet coaches found that, if an athlete spent too much time in a single camp, they began to plateau or even drop in performance. These coaches decided to allow athletes to spend time at home resting, or send them to different camps to develop different skill sets. These coaches found that the variation of training and/or rest time allowed athletes to continue making progress rather than plateauing. And thus, a possible birth of periodization.

- Another theory that stems from the Soviet Union (and connects to Theory 3) is the fact that Russia isn’t exactly the sunniest country in the world. Periodization has its roots in the 1950s when the Soviet Union was recovering from World War II – athletic training facilities in the 1950s Soviet Union were, then, few and far in between and could easily reach maximal capacity. Due to this issue, Soviet coaches would plan sport training depending on the seasons. In late spring and summer, summer Olympic athletes would perform their outdoor training while the weather cooperated whereas winter Olympic athletes would stay indoors and train different skill sets. When the seasons switched, so did the athletes. And thus, planned variation due to weather and facility availability.

- Due to Theory 2, some people have simply linked “chronobiology” to periodization with the theory that the human body simply adapts differently during different seasons. If one were to prescribe to this theory, planned training variation would depend on the seasons, rather than other training variables. I’m not a huge subscriber to this thought for a few reasons, but chronobiology is also a newer realm of science when it comes to human performance. I’m definitely keeping my eyes peeled for trials considering seasonal effects on training gains.

- The last theory seems to be the most popular in Western countries. This theory is developed off of the General Adaptation Syndrome model by Hans Selye. Essentially, this model describes an organism’s reaction and adaptation to an outside stimulus. It was originally developed using rodents and various types of poisons or medications, but many researchers have connected it to training and human performance. One reason for this connection is the biological Law of Accommodation, which states that an organism’s response to a specific stimulus is diminished over time if the stimulus does not change. In gym speak, if you always just do 3×10 at 135lbs on bench, you’re not going to make great long-term gains. Planning variation would be a necessary component of a training program according to these biological models.

So, we have some of the primary theories out of the way. Why is periodization such a big deal then? Obviously Soviet coaches (and others soon after) were seeing improvements in athletic performance, so what gives?

Periodization Theory and Models

The initial purpose of periodization was to allow for maximal athletic performance on a single given competition date that was months or years down the road. This is why periodization was initially developed with Olympic athletes – these individuals, for all intents and purposes, have 4-year training cycles. Programming, then, would have to reflect the goal of displaying maximal ability at the Olympics, rather than other dates throughout that 4-year period.

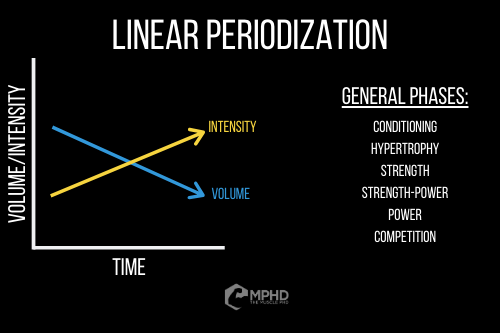

With this in mind, linear periodization quickly took off. The idea of linear periodization can be simplified relatively easily – essentially you reduce volume and increase intensity as you move closer to the event. We often see this reflected in programs where you start off with a general conditioning phase, then move to hypertrophy (or strength-endurance), then to strength, then to strength-power (or maximal strength), and lastly, power. This model is perfect for individuals tapering to a single event that is highly reliant on muscle power rather than other skills. Therefore, athletes like jumpers, sprinters, throwers, and weightlifters greatly benefitted from linear periodization in the early days. It’s no surprise, then, that Eastern Bloc countries dominated these events in the 1950s and 1960s. Drugs also probably played a role, but that’s outside the scope of this piece.

With this in mind, linear periodization quickly took off. The idea of linear periodization can be simplified relatively easily – essentially you reduce volume and increase intensity as you move closer to the event. We often see this reflected in programs where you start off with a general conditioning phase, then move to hypertrophy (or strength-endurance), then to strength, then to strength-power (or maximal strength), and lastly, power. This model is perfect for individuals tapering to a single event that is highly reliant on muscle power rather than other skills. Therefore, athletes like jumpers, sprinters, throwers, and weightlifters greatly benefitted from linear periodization in the early days. It’s no surprise, then, that Eastern Bloc countries dominated these events in the 1950s and 1960s. Drugs also probably played a role, but that’s outside the scope of this piece.

However, what if you’re not an Olympic athlete with one major event only every 4 years? What if you compete every week like an American football player? Is linear periodization the way to go?

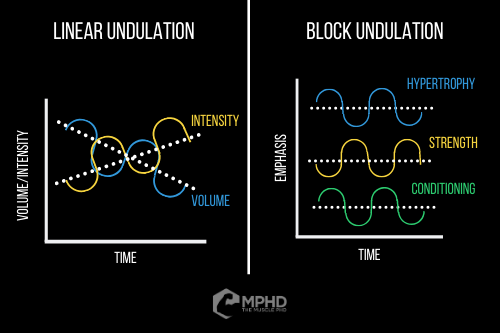

A major drawback of linear periodization is that it’s not great for training multiple skills at once. In this instance, a “skill” would be considered muscle strength, endurance, size, or power. As you can see in the pictures, linear periodization mostly focuses on one single skill in each training phase. So, what happens as you progress towards the later stages? You begin to lose adaptations from the initial stages. Now, that’s fine if you’re an Olympic power athlete, but would an American football player want to lose conditioning as the season progressed? Would they be fine losing some muscle strength or mass? I don’t think so.

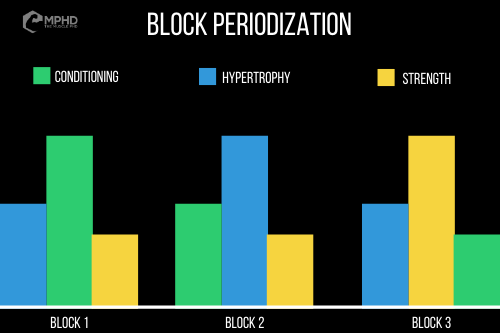

With these shortcomings in mind, coaches began to develop different periodization models to fit the needs of non-Olympic sport athletes. The most notable and commonly-used model in this instance is “Block Periodization.” Block periodization has similar phases (or blocks) to linear periodization; however, the block “title” is just the emphasis of a block. Let’s say you’re in a strength block in this model – you’d probably spend 50-60% of your time on strength training variables, but the other 40-50% of your training volume would come from training variables meant to develop or maintain other skills. While this model may not maximize adaptations to the given emphasis in each block, it’s much better at maintaining performance of multiple skills at once – which is incredibly important to non-Olympic athletes.

With these shortcomings in mind, coaches began to develop different periodization models to fit the needs of non-Olympic sport athletes. The most notable and commonly-used model in this instance is “Block Periodization.” Block periodization has similar phases (or blocks) to linear periodization; however, the block “title” is just the emphasis of a block. Let’s say you’re in a strength block in this model – you’d probably spend 50-60% of your time on strength training variables, but the other 40-50% of your training volume would come from training variables meant to develop or maintain other skills. While this model may not maximize adaptations to the given emphasis in each block, it’s much better at maintaining performance of multiple skills at once – which is incredibly important to non-Olympic athletes.

Block periodization can also be somewhat linear as you can move down the linear phase chart by emphasizing one skill at a time. However, you’ll still be devoting nearly 50% of your training time to other skills so it won’t be nearly as linear as true linear periodization.

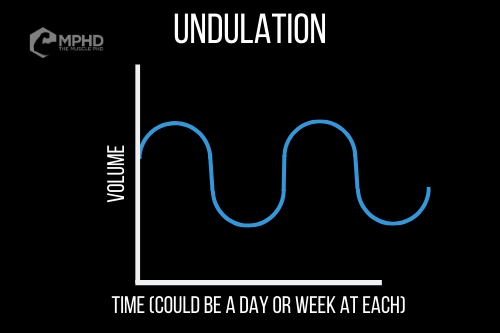

Lastly, within both linear and block models, we often see something called “undulation.” Undulation in a training program can be visualized as a waveform that represents training volume – this volume can be monthly, weekly, or even daily depending on how often it changes. Undulating volume can be beneficial for a few things:

- It reduces training monotony which can ward off overtraining.

- It ensures constant variation which appeases the Law of Accommodation.

- Higher training volumes might also maximize adaptations in slow twitch muscle fibers in conjunction with lower/heavier volumes mostly impacting fast twitch muscle fibers.

Undulation can also be incredibly important for athletes as it allows coaches to plan training volumes around competition periods. This is common in collegiate American football where training volume (both practice and strength training) will peak in the middle of week, then let off on Friday before the big game on Saturday.

Undulation can also be incredibly important for athletes as it allows coaches to plan training volumes around competition periods. This is common in collegiate American football where training volume (both practice and strength training) will peak in the middle of week, then let off on Friday before the big game on Saturday.

Ultimately, the goal of any periodization plan is to ensure that maximal performance is possible on the desired date of competition. Therefore, the periodization model you choose to employ is pretty dependent on when/how often your competition is as well as what types of “skills” you need to display in competition. With this in mind, how relevant is periodization to bodybuilding?

How Does This Relate to Bodybuilding?

Let’s first discuss competitive bodybuilding:

As a competitive bodybuilder, it’s certainly true that you will have 1-3 competitions every year that you’re hoping to compete at your best in. However, what athletic “skill” is really portrayed in a bodybuilding show? When you step on stage, you’re often pretty weak from dehydration and low calories. Your muscles certainly aren’t as big as they were before you got absolutely peeled. Odds are, you have very little muscle power from both dehydration and being shredded.

With this in mind, linear periodization is mostly pointless in bodybuilding. Your goal is to display your physique, not muscle power. Power training really has little to no place in bodybuilding in general as it does nothing for muscle size. It might help neuromuscular adaptations which could help growth in the long term, but for experienced bodybuilders, that’s probably a moot point.

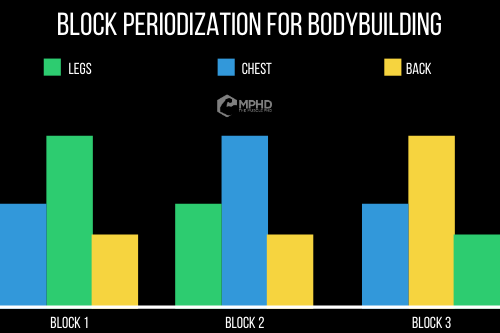

So, if linear periodization is out, what about block periodization? Again, we have to consider what types of “skills” we want to develop throughout a bodybuilding training program. It’s mostly muscular size and strength. So, your “blocks” as a bodybuilder would mostly rotate between strength emphasis and size emphasis. With the relatively few skills being trained in bodybuilding, I like to create blocks for individual muscle groups to be an emphasis rather than a “skill.” With this in mind, you can really emphasize your legs, for example, while maintaining other muscle groups. Let’s say you run this block for 4-weeks and then switch to a chest emphasis for 4-weeks, etc. Really, a lot of high-level bodybuilders do this and probably don’t even realize they’re performing a “bro-ish” version of block periodization.

So, if linear periodization is out, what about block periodization? Again, we have to consider what types of “skills” we want to develop throughout a bodybuilding training program. It’s mostly muscular size and strength. So, your “blocks” as a bodybuilder would mostly rotate between strength emphasis and size emphasis. With the relatively few skills being trained in bodybuilding, I like to create blocks for individual muscle groups to be an emphasis rather than a “skill.” With this in mind, you can really emphasize your legs, for example, while maintaining other muscle groups. Let’s say you run this block for 4-weeks and then switch to a chest emphasis for 4-weeks, etc. Really, a lot of high-level bodybuilders do this and probably don’t even realize they’re performing a “bro-ish” version of block periodization.

Lastly, what about undulation? We’ve seen several times in research that undulated training programs are a little better for promoting gains in muscle size than linear programs. Again, this likely has to do with the fact that a linear program only performs appropriate volume for maximizing muscle growth in a small portion of the big picture. Meanwhile, an undulated program might get a good growth stimulus out of 70-80% of workouts. Why is this the case? Refer to one of our points on undulation from above – combining very high training volumes with very low (say 3×20 vs. 3×3, for instance) can maximize training adaptations and growth in both slow twitch and fast twitch muscle fibers. These may be rather small differences, but for a competitive bodybuilder, those differences can add up over the years and help someone make the transition from top 10 to top 3.

Lastly, what about undulation? We’ve seen several times in research that undulated training programs are a little better for promoting gains in muscle size than linear programs. Again, this likely has to do with the fact that a linear program only performs appropriate volume for maximizing muscle growth in a small portion of the big picture. Meanwhile, an undulated program might get a good growth stimulus out of 70-80% of workouts. Why is this the case? Refer to one of our points on undulation from above – combining very high training volumes with very low (say 3×20 vs. 3×3, for instance) can maximize training adaptations and growth in both slow twitch and fast twitch muscle fibers. These may be rather small differences, but for a competitive bodybuilder, those differences can add up over the years and help someone make the transition from top 10 to top 3.

So, block periodization with a good amount of undulation is probably a better model for the competitive bodybuilder. Now, there will still be a linear component since training volume will be reduced as you get closer to competition – when your recovery capacity is diminished from lack of food, you’re going to have to drop training volume. However, training intensity (weight used or % 1RM) shouldn’t drop much as you still want to maintain as much muscle as possible.

Now let’s talk about recreational (non-competitive) bodybuilders:

You have no competition in sight. You have no need to maximally display your physique besides things like spring break, etc. where you want to look killer on the beach. With this in mind, linear periodization methods are pretty much completely out. There’s no need to systematically reduce training volume while increasing/maintaining intensity. Unless you want to dominate in a recreational softball league – but that’s outside the scope of this piece.

With this in mind, most recreational bodybuilders can probably also rely on some sort of block periodization. But, with general fitness goals in mind, adding things like conditioning or power blocks can also be useful for simply improving overall fitness. If muscle growth/strength isn’t your sole goal from training, adding in these additional blocks can help improve your overall “physical shape.”

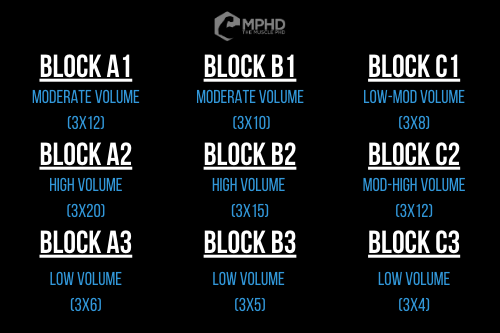

Again, we’d still recommend some sort of undulation with a program such as this as you’ll want to keep a decent amount of volume variation to avoid any staleness in your training. Since I would consider myself a recreational bodybuilder at the moment, here’s an idea of my training program:

Again, we’d still recommend some sort of undulation with a program such as this as you’ll want to keep a decent amount of volume variation to avoid any staleness in your training. Since I would consider myself a recreational bodybuilder at the moment, here’s an idea of my training program:

Basically, the way this works is that I go through all of my Block A workouts, then Block B, and then block C. I do a legs-push-pull split with a rest day after legs and a rest day after pull. So, for my major exercises in each block, I’m doing 3-4 sets of the volume-based reps per set. This means I have 5 total days within each sub-block (3 training and 2 rest days). I’ll do 3×12 on all my major movements during Block A1, then I’ll move to 3×20 for major movements in Block A2, and so-on and so-forth. This is an easy example of block periodization as I can tailor my accessory/isolation movements to whatever goals I want while my main movements (squat, bench, deadlift and variations) are within the parameters of the Block volume. This plan also forces undulation in that I’m doing a new volume block every 5 days – this keeps a lot of variation within the program and allows for tons of progressive overload opportunities when you repeat the cycle.

I often alternate exercises on these as well. For instance, I usually alternate bilateral and unilateral leg days as well as barbell- vs. dumbbell-based push days. Keeping these rotations in mind can also really force you out of your comfort zone – i.e. I had to do 3×15 on squats the other day. Usually I’d stick to a hack squat for higher rep sets but doing barbell squats was a whole new stimulus and crushed me. It was great! I won’t go into too much detail here as a lot of my training is also based on feel rather than planning – but simply having some sort of undulating plan for your general volume can absolutely spice up your training and help you make new gains.

Lastly, there’s still a small linear aspect to this program as well as the volume will drop as you move through blocks. The main reason for this is that fatigue will accumulate throughout this program, so the final block can almost act as a volume deload before you start over again. Since I’m not peaking for a specific competition, these three phases work pretty well for me.

Takeaways and Conclusion

Ultimately, the classic model of periodization (linear) isn’t overly applicable to bodybuilding. There are several models that would likely be more useful, and we’ve presented a combination of two in this piece. Block periodization with some sort of undulation, whether it be weekly or daily, is probably going to help maximize gains, no matter what type of bodybuilder you are. You can stick to a general plan like I outlined above or you can go all-out and plan every single set and rep of each exercise as you go along. Whatever works for you and keeps you motivated to train!

Keep your eyes peeled as we’ll likely draft and (hopefully) publish a hefty review on this topic sometime within the next year or two. Like mentioned above, the majority of periodization literature is geared towards sport athletes looking to display maximal athleticism in a given number of planned events. Since that doesn’t really represent bodybuilders, we’ll need to dig further into the research and theories to present something a little more complex than what’s in this piece. Hopefully it’ll serve the community well and might point us towards more future research questions!

From being a mediocre athlete, to professional powerlifter and strength coach, and now to researcher and writer, Charlie combines education and experience in the effort to help Bridge the Gap Between Science and Application. Charlie performs double duty by being the Content Manager for The Muscle PhD as well as the Director of Human Performance at the Applied Science and Performance Institute in Tampa, FL. To appease the nerds, Charlie is a PhD candidate in Human Performance with a master’s degree in Kinesiology and a bachelor’s degree in Exercise Science. For more alphabet soup, Charlie is also a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), an ACSM-certified Exercise Physiologist (ACSM-EP), and a USA Weightlifting-certified performance coach (USAW).